Introducing my Military Realism Reports

Hi there folks. This week I’ve been working on something different. Instead of my usual 2-3k word article, I’ve been putting together a longer piece on “How Guns Work.” This is the first in what I hope will be a many longer-form explainer web-pages.

These will be a hybrid of fresh new content and consolidated, curated versions of some previous blog content. So please excuse me if you see something again, and don’t feel bad about skipping it over if you’ve seen it already.

This blog post will cover the first four chapters of the full page, but there are eleven chapters in all, and I may add more in due course. Check out the full page on the Realism Reports section of the site: How Guns Work.

Before we start, let me encourage you to subscribe to the blog using the link below. As always, I’d love to see your comments below, or you can contact me via webform here or email here. Finally, if you’ve enjoyed this post, please share it with a friend.

If you enjoy this blog and want to support it, please consider a donation. Keeping this blog going doesn’t cost much, but it isn’t free either, so any help would be very much appreciated👍

Introduction

Firearms are a staple of movies and TV shows. Whether it’s an action flick, a war movie, or a police procedural, the heroes and villains rely on guns to achieve their goals (and to drive the plot forward).

Despite their ubiquity on screen, however, there’s a dearth of simple, plain English information about how they work. Sure, there’s plenty of content out there about guns1. But it tends to be either too basic for words or else so wrapped up in nerdish jargon that a layperson would run a mile before trying to make sense of it.

I was a professional military Ordnance engineer for the better part of a decade. This means that I know what I’m talking about (up to a point) but it’s not an obsession. I think—I hope—this means I’ve got enough knowledge to make this informative but not enough skin in the game to make it dull. Let’s see how I do.

In this article I’m going to stick to what we call “small arms,” which is usually defined as anything of calibre 12.7 mm (0.5 inch2 or “50 cal[ibre]”) and below. Don’t know what these words mean? Don’t worry, all will be explained.

Different types of gun (prologue)

Let’s start by classifying guns. You’re probably aware of the different types, so we don’t need to spend too long on this. Here’s a classification by “form factor,” which is a fancy way of saying “what it looks like.” Form factor is one of the easiest ways to categorise guns, or anything, for that matter. That’s because we know what sorts of things look like each other, even if we don’t have the foggiest idea how they work.

That’s quite simple, but already you can see some areas of ambiguity. Are rifles and shotguns classified together as “long guns,” or do they look different enough to get their own categories? What about the two weapons below: both are rifles, but they sure as hell don’t look the same (and they behave very differently too).

It doesn’t really matter what’s on the diagram above, because anyone with an opinion on guns will almost certainly disagree. That’s okay, but it’s a useful starting point. Especially if you’ve never seen a Hollywood movie before. Let’s take a step back, now, and look at the physics behind firearms.

The naming of parts

Every weapon lesson starts with the naming of parts. This is where you need to learn the difference between the “retaining bolt spring” and the “retaining spring bolt” before you ever get to actually fire the thing. I’m not going to do that to you. I’m also not going to let you fire.

Instead, I want to define some of the basic terms I’ll be using later on:

- Barrel: the bit you point at the enemy. The bullet comes out of here.

- Bolt: the bit of machinery inside which guides the cartridge into the barrel, holds it in place during firing, and takes it out afterward.

- Breech: the back (where the barrel meets the bolt)

- Bullet: part of the “round”, this is the actual projectile that goes toward the target very fast

- Cartridge: the part of the round that contains the bullet

- Chamber: the start of the barrel

- Magazine: where the rounds are kept (see also: “bullets” above and “rounds” below)

- Moving parts: the bolt and anything else which moves with it during automatic fire

- Muzzle: the front

- Receiver: the main body of the gun

- Round: the name given to the bullet and cartridge case forming a complete unit before firing

The fundamental physics of firearms

Firearms are weapons. I think that’s a useful starting point, because everyone can agree3 with it. What’s the point of a weapon? It’s something which you use to inflict damage on another person or animal. More specifically, it’s something you use to increase your damage effectiveness. It’s a damage multiplier: something which any gamer will be know all about. Without weapons, we would be limited to fighting like this:

In fact, even without weapons, we know instinctively how to concentrate our energy when fighting. That’s why we use our fists or feet against an opponent’s head or other vulnerable parts, instead of smashing our own head against it (unless you’re a deer or have the defective Simpsons gene).

Once man discovered tools, we had a way to concentrate even more energy into a single point when attacking a person or animal. Stones added weight to our blows and bones added leverage (or sticks, more likely). The rest is history, as Stanley Kubrick showed us in 2001: A Space Odyssey:

The discovery of bronze and later iron enabled us to channel all of a single person’s energy into a single point (spear) or edge (sword or axe), easily penetrating the weak defences of the human body.

Then came arrows and bolts, which are great because they let you concentrate the same energy you’d get in the tip of a spear, but send it many dozens of metres away. Now you can deliver the same deadly point source of energy into your enemy from a safe distance.

This is great, at least until your enemy realises the same thing and makes a bow and arrow of his own. A crossbow and bolt ups the ante even more by using levers and pulleys and mechanical advantage to store way more energy in the weapon than you could normally put in by muscle power alone4. This means that the bolts fly farther and pierce more armour when they get there.

Then we get bullets. Bullets are the next step in this energy concentration arms race. They are an amazing innovation because they allow the firer to use someone else’s energy, not just their own. That makes a very big difference.

The first gunpowder (black powder, to be precise) was a mixture of potassium nitrate, sulphur, and charcoal. Potassium nitrate sounds very fancy, but it was often extracted from human or animal dung in no-doubt fragrant saltpetre works.

Gunpowder was amazing stuff. One kilogram (about two pounds) of the stuff released as much energy in a fraction of a second as a person can exert in eight hours of manual labour. Each shot’s worth of powder takes several minutes of notional hard work and sends it out in an instant6.

It’s only gotten better since then. Modern propellants and high explosives contain about as much energy as some common and delicious foods, but release them much more quickly:

It’s all about the rate of energy release. Nuclear reactions happen over nanoseconds, high explosives take microseconds to react, propellants in guns are a thousand times slower still, and food takes anywhere from minutes to decades to convert all its chemical energy to useful work.

What’s a gun, then? It’s a machine which converts the magical free energy in chemical propellants into kinetic (movement) energy of a bullet. Why? So that the kinetic energy in the bullet can hit a target and do some kind of damage. How? That’s the magic of weapons design and engineering.

Let’s say we want to inflict more damage on our target (person or animal, remember? Not all guns are bad, all the time). How do we do this? We have three options:

- Get a better propellant. We could use something to propel our bullet which has even more energy. Modern propellants pack roughly twice as much energy into themselves, grain for grain7, as black powder. But we can only go so far with this approach, and inventing new chemicals is hard.

- Pack more propellant behind the bullet. This is a popular approach. More “bang” means more sonic boom… but only up to a point. You can only do this within the design limits of the gun itself. Worst case scenario, more propellant makes the back end or the barrel explode (see photo below). Best case, you just waste a bunch more energy as heat and gases rather than useful kinetic energy in the bullet.

- Make the gun more efficient. This is where the real tricky engineering comes in. A longer barrel with a tighter seal, for example, means that the bullet picks up more energy from the gases as it’s pushed along. Making things tight is hard, though. Manufacturing barrels is a very niche capability.

If we get that last part right, then the gun is as efficient as possible. No matter how hard we try, however, we would struggle to get more than 30% of the propellant energy into that bullet.

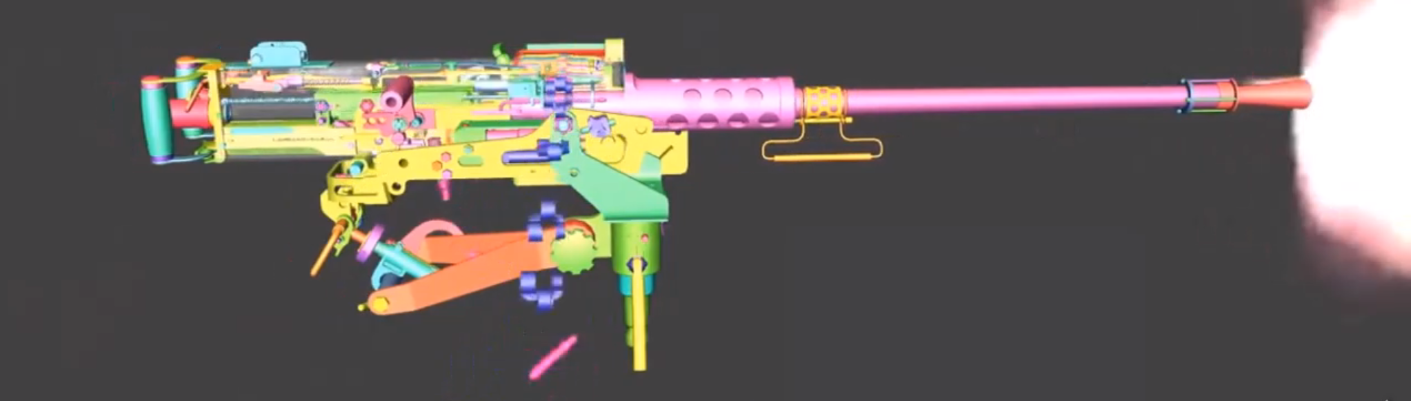

As you can see above, a portion of the energy can be used to cycle the weapon. This leads us into the next section, where we’ll look at how the machinery of guns works to turn a single violent action into a reliable and repeatable series of them.

Do you like this explainer so far? Read the rest on the Realism Reports section of the site: How Guns Work.

Thanks for reading and please remember, if you haven’t already, to subscribe using the link below. Please also share this article with a friend and help me broaden my reach. Every little helps! See you next week.

Cover picture: This is how M2 Browning Works, ALTIN GAMING, via YouTube

- Here are just a few examples:

https://www.nrafamily.org/content/how-do-guns-work-part-1/

https://youtu.be/flYYG65yW5I?si=ZOIcjexNHZysrX60&t=110

https://www.reddit.com/r/explainlikeimfive/comments/bwrhvi/eli5_how_do_guns_work/

https://www.luckygunner.com/lounge/blowback-versus-recoil/ ↩︎ - I’m a proper freedom-hating European, but I’m comfortable with Imperial units. Honestly. ↩︎

- <Sigh>. Yes, I see you over there, powder actuated tools, raising your hand. There’s always one, isn’t there? ↩︎

- Because, and this may be news to you if you’ve never used one, but pulling back the string on a bow is hard. It’s supposed to be. It’s how an arrow can get lots of speed. It’s why, as Bret Devereaux on ACOUP points out, these scenes of fantasy or ancient battles where archers “volley fire” are pure nonsense. ↩︎

- Prompt: “Can you make me four simple powerpoint icons please? They should be black on white background. They are: 1) An ancient spearman 2) An ancient archer firing his bow and arrow 3) A medieval crossbowman 4) An early modern musketman” ↩︎

- Rough assumptions: energy density of black powder is 3 MJ/kg, a person works about 2,250 kcal per day (~9 MJ), and a musket load of powder is about 90 grains, or 5 grammes. ↩︎

- In firearms engineering, a “grain” has actual meaning. It’s a measure of weight equivalent to about 0.065 grammes. It was on old Imperial unit used for other measurements back in the day, but that day has passed: now you see it only to weigh bullets and bullet propellant loads. ↩︎

Leave a Reply