Introduction

Firearms are a staple of movies and TV shows. Whether it’s an action flick, a war movie, or a police procedural, the heroes and villains rely on guns to achieve their goals (and to drive the plot forward).

Despite their ubiquity on screen, however, there’s a dearth of simple, plain English information about how they work. Sure, there’s plenty of content out there about guns1. But it tends to be either too basic for words or else so wrapped up in nerdish jargon that a layperson would run a mile before trying to make sense of it.

I was a professional military Ordnance engineer for the better part of a decade. This means that I know what I’m talking about (up to a point) but it’s not an obsession. I think—I hope—this means I’ve got enough knowledge to make this informative but not enough skin in the game to make it dull. Let’s see how I do.

In this article I’m going to stick to what we call “small arms,” which is usually defined as anything of calibre 12.7 mm (0.5 inch2 or “50 cal[ibre]”) and below. Don’t know what these words mean? Don’t worry, all will be explained.

Different types of gun (prologue)

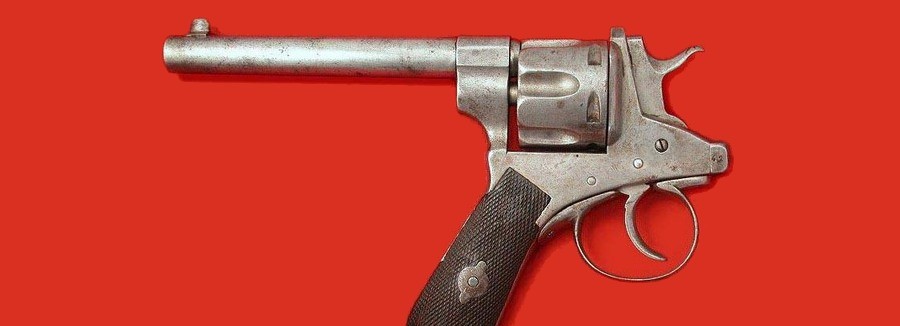

Let’s start by classifying guns. You’re probably aware of the different types, so we don’t need to spend too long on this. Here’s a classification by “form factor,” which is a fancy way of saying “what it looks like.” Form factor is one of the easiest ways to categorise guns, or anything, for that matter. That’s because we know what sorts of things look like each other, even if we don’t have the foggiest idea how they work.

That’s quite simple, but already you can see some areas of ambiguity. Are rifles and shotguns classified together as “long guns,” or do they look different enough to get their own categories? What about the two weapons below: both are rifles, but they sure as hell don’t look the same (and they behave very differently too).

It doesn’t really matter what’s on the diagram above, because anyone with an opinion on guns will almost certainly disagree. That’s okay, but it’s a useful starting point. Especially if you’ve never seen a Hollywood movie before. Let’s take a step back, now, and look at the physics behind firearms.

The naming of parts

Every weapon lesson starts with the naming of parts. This is where you need to learn the difference between the “retaining bolt spring” and the “retaining spring bolt” before you ever get to actually fire the thing. I’m not going to do that to you. I’m also not going to let you fire.

Instead, I want to define some of the basic terms I’ll be using later on:

- Barrel: the bit you point at the enemy. The bullet comes out of here.

- Bolt: the bit of machinery inside which guides the cartridge into the barrel, holds it in place during firing, and takes it out afterward.

- Breech: the back (where the barrel meets the bolt)

- Bullet: part of the “round”, this is the actual projectile that goes toward the target very fast

- Cartridge: the part of the round that contains the bullet

- Chamber: the start of the barrel

- Magazine: where the rounds are kept (see also: “bullets” above and “rounds” below)

- Moving parts: the bolt and anything else which moves with it during automatic fire

- Muzzle: the front

- Receiver: the main body of the gun

- Round: the name given to the bullet and cartridge case forming a complete unit before firing

The fundamental physics of firearms

Firearms are weapons. I think that’s a useful starting point, because everyone can agree3 with it. What’s the point of a weapon? It’s something which you use to inflict damage on another person or animal. More specifically, it’s something you use to increase your damage effectiveness. It’s a damage multiplier: something which any gamer will be know all about. Without weapons, we would be limited to fighting like this:

In fact, even without weapons, we know instinctively how to concentrate our energy when fighting. That’s why we use our fists or feet against an opponent’s head or other vulnerable parts, instead of smashing our own head against it (unless you’re a deer or have the defective Simpsons gene).

Once man discovered tools, we had a way to concentrate even more energy into a single point when attacking a person or animal. Stones added weight to our blows and bones added leverage (or sticks, more likely). The rest is history, as Stanley Kubrick showed us in 2001: A Space Odyssey:

The discovery of bronze and later iron enabled us to channel all of a single person’s energy into a single point (spear) or edge (sword or axe), easily penetrating the weak defences of the human body.

Then came arrows and bolts, which are great because they let you concentrate the same energy you’d get in the tip of a spear, but send it many dozens of metres away. Now you can deliver the same deadly point source of energy into your enemy from a safe distance.

This is great, at least until your enemy realises the same thing and makes a bow and arrow of his own. A crossbow and bolt ups the ante even more by using levers and pulleys and mechanical advantage to store way more energy in the weapon than you could normally put in by muscle power alone4. This means that the bolts fly farther and pierce more armour when they get there.

Then we get bullets. Bullets are the next step in this energy concentration arms race. They are an amazing innovation because they allow the firer to use someone else’s energy, not just their own. That makes a very big difference.

The first gunpowder (black powder, to be precise) was a mixture of potassium nitrate, sulphur, and charcoal. Potassium nitrate sounds very fancy, but it was often extracted from human or animal dung in no-doubt fragrant saltpetre works.

Gunpowder was amazing stuff. One kilogram (about two pounds) of the stuff released as much energy in a fraction of a second as a person can exert in eight hours of manual labour. Each shot’s worth of powder takes several minutes of notional hard work and sends it out in an instant6.

It’s only gotten better since then. Modern propellants and high explosives contain about as much energy as some common and delicious foods, but release them much more quickly:

It’s all about the rate of energy release. Nuclear reactions happen over nanoseconds, high explosives take microseconds to react, propellants in guns are a thousand times slower still, and food takes anywhere from minutes to decades to convert all its chemical energy to useful work.

What’s a gun, then? It’s a machine which converts the magical free energy in chemical propellants into kinetic (movement) energy of a bullet. Why? So that the kinetic energy in the bullet can hit a target and do some kind of damage. How? That’s the magic of weapons design and engineering.

Let’s say we want to inflict more damage on our target (person or animal, remember? Not all guns are bad, all the time). How do we do this? We have three options:

- Get a better propellant. We could use something to propel our bullet which has even more energy. Modern propellants pack roughly twice as much energy into themselves, grain for grain7, as black powder. But we can only go so far with this approach, and inventing new chemicals is hard.

- Pack more propellant behind the bullet. This is a popular approach. More “bang” means more sonic boom… but only up to a point. You can only do this within the design limits of the gun itself. Worst case scenario, more propellant makes the back end or the barrel explode (see photo below). Best case, you just waste a bunch more energy as heat and gases rather than useful kinetic energy in the bullet.

- Make the gun more efficient. This is where the real tricky engineering comes in. A longer barrel with a tighter seal, for example, means that the bullet picks up more energy from the gases as it’s pushed along. Making things tight is hard, though. Manufacturing barrels is a very niche capability.

If we get that last part right, then the gun is as efficient as possible. No matter how hard we try, however, we would struggle to get more than 30% of the propellant energy into that bullet.

As you can see above, a portion of the energy can be used to cycle the weapon. This leads us into the next section, where we’ll look at how the machinery of guns works to turn a single violent action into a reliable and repeatable series of them.

Repeating the action: how to shoot more than once

It’s one thing to use chemical energy to propel a bullet toward your target. It’s quite another thing to do so again and again and again. Modern assault rifles and machine guns can fire hundreds of thousands of rounds before failing if they’re used and maintained correctly (which is a big if). Pistols might last a million cycles or more.

It wasn’t always like this. For at least six hundred years of European warfare, reloading firearms was a slow and technical process. Armies learned to break it up into standard drill movements so that a soldier could do it even in the heat and confusion of battle.

In the middle of the 19th century a new innovation in weapon design—the integrated, metallic cartridge—enabled infantrymen to go from firing several rounds per minute to a dozen or more. This technology, and the machine gun which came later and built on the same idea, changed the tactics of infantry combat from massed close-order formations of firepower to looser, dispersed pockets of men moving under cover and concealment. You can read more about this in my “Art of Camouflage” article.

Let’s take a second to describe what we mean by “integrated, metallic cartridge,” by comparing it to what went previously:

The cartridge allowed weapons designers to standardise the machinery of firearms and make it more complex while still being reliable. This led to a range of innovations in how to allow guns to fire over and over again.

Manual action

The most basic innovation was the ability to quickly reload each round. Engineers could now make weapons which, with one smooth mechanical action, cycled a fresh round into the chamber (the start of the barrel) for firing.

With a simple two or three second hand action, a firer could reload a fresh round ready for the next shot:

You can see another beautifully animated clip here by Nicholas Rudowski (scroll down to the adjustable timeline view).

There are other ways to manually cycle a weapon: with a lever, a slide action (usually seen on pistols) or a pump action (usually, but not always, for shotguns):

Manual action may seem basic as hell, but it’s a huge improvement over having to load powder and ball and wadding as separate components via the muzzle of the gun. Many modern weapons still use manual action. For example, sniper rifles, where simplicity and reliability are priorities and rate of fire is not, are often bolt action.

Blowback operation

We saw above how only 30% of the chemical energy in the propellant ends up going into bullet velocity. This means there’s wasted energy in terms of propellant gases and heat. Gun designers have the option to use some of this energy to replace the manual actions we discussed above, and make the weapon automatically feed a new round and start a new cycle.

The simplest way of doing this is with “blowback” action. As the name suggests, this involves using the propellant gases from the cartridge to do work in two directions: rather than simply accelerate the bullet out of the barrel, they also accelerate the bolt (brown in the GIF below) or moving parts of the weapon rearward to eject the spent round and cycle a new one.

Blowback operation has the wonderful virtue of being simple: it doesn’t require many moving parts like some of the mechanisms described below. This is why it’s popular in many pistols and submachine guns: small weapons with small rounds.

It does have a limitation, however. As rounds get bigger, with more propellant in the cartridge, the blowback force gets stronger. This means that it accelerates the bolt more, unless you make the bolt bigger and heavier to compensate (because heavier things take longer to accelerate). The problem with a faster bolt is that it might let the cartridge come back out of the barrel before all the propellant gases have burned.

This would mean hot gases would come out of the back of the weapon, bringing lots of bits of brass and loose parts of the weapon itself. The firer would end up with bits of metal sticking out of their face.

There are some clever ways around this, such as introducing little widgets which delay blowback until the gas pressure in the barrel has reached a safe level. Another option is recoil operation; let’s talk about that next.

Recoil operation

When a gun fires, a force is exerted on the bullet by the propellant gases. This is what makes it accelerate down the barrel, and is generally regarded as a good thing (unless you’re on the other side of the barrel). But because of Newton’s Third Law of motion, this means that the bullet exerts an equal and opposite force on the gun. This is known as recoil, and is sometimes regarded as a bad thing (because it makes guns hard to hold and control when firing).

Clever gun designers can use this recoil to their benefit, however. Instead of letting the whole gun recoil, they can fit the barrel and bolt to the receiver. That way the recoil force from the escaping bullet can act on the barrel and bolt alone and make them move relative to the receiver.

The key difference between blowback and recoil operations is that, in the latter, the bolt remains locked to the barrel until the gas pressure in the barrel has reached a safe level.

Once this safe level is reached, these weapons use some sort of mechanical linkage to then disconnect the barrel from the bolt and allow the spent cartridge to expend. The iconic Browning M2, a design which dates from pre-WWII, uses accelerator “horns” to convert the “slow” motion of the barrel moving rearward into a faster motion for the rest of the moving parts. Look out for the pink finger-shaped items in the lower centre of the animation below:

Gas operation

Since so much propellant gas is wasted in normal firing, surely it makes sense to use some of this to cycle the weapon? Gas operated weapons make use of this principle.

As the expanding propellant gases rush down the barrel, pushing the bullet along on its merry way, some of them find a hole and a little antechamber to the main barrel and get turned around. While on this side quest, the propellant gases encounter another piston or cup or other obstruction which they, quite naturally, try to push out of their way.

It’s this force on a piston or cup or rod which moves the “actions” to the rear, ejecting the old round and letting the springs bring them forward again to chamber a new round.

Look at this amazing animation of how a Steyr AUG‘s gas operation works. You’re looking for the small grey piston and spring at the right-hand side of the frame. You might find it hard to believe that a short stroke from such a tiny piston can move the heavy springs of the actions all the way back. Believe me, I puzzled over this for years. If that component looks small on the animation, if feels even smaller and less substantial when you’re holding it.

Guns are all about extreme engineering, though, and we’ll cover this topic in a bit more detail further down.

In the meantime, if you’re confused about the difference between blowback, gas operation, and recoil, this image sums them up nicely:

There are disadvantages to gas operation. The gas itself is full of soot and can foul up the inner workings of the weapon. Using blank rounds with a gas operated weapon is a nightmare because there’s never quite enough oomph to cycle the weapon properly, no matter what kind of modifications you make to the barrel.

We could dispense with gas altogether and use an external source of power. After all, energy is not something we’re short of in modern technology.

External power

A chain gun uses an external source of power (e.g. electric) to drive its internal mechanisms. It loads shells, fires them, ejects them, and loads a fresh shell based on a predictable and controllable cycle.

The mechanism of a chain gun isn’t tied to the energy of the propellant in the rounds, unlike the other forms of automatic fire discussed above. It relies solely on the power feed from (usually) the vehicle which it’s mounted on.

Below is a video of the Mk44 Bushmaster 30 mm chain gun. It’s stripped open and with key parts removed so you can see its innards (anywhere you see red paint is a “removed” section; this weapon will never actually fire).

The instructors are slowly actuating the chain using a wrench: this would normally be done by an electric motor and at much greater speed.

An advantage of external power is that the gun isn’t reliant on the quality of the ammunition for its operation. If a gas, recoil, or blowback weapon suffered a misfire, the gun would stop working until the firer manually cleared the misfired round and cycled in a fresh one. Not so with a chain gun: the offending round will be extracted and ejected as if it had fired, and a fresh one will be in the chamber before anyone even notices.

Automatic vs. Semi-automatic fire

It’s worth pausing at this stage to make a distinction between mode of operation (which we’ve just discussed) and automatic vs. semi-automatic vs. single shot fire.

In theory, any weapon which can load a fresh round by itself (i.e. blowback, recoil, gas-operated, or externally powered) should be able to operate in fully automatic mode. In practice, some weapons are limited by design to fire only single shots.

Firing single shots with an automatic re-chambering of the next round in between is known as semi-automatic fire. Fully automatic, therefore, is when you hold down the trigger and the bullet keep flying until you run out of ammunition. Speaking of which…

Magazines and the myth of the “clip”

A critical but often overlooked component in all the mechanisms we discussed above is the magazine: the box which holds all your rounds. This needs to provide enough spring tension to the column of rounds above it so that they feed seamlessly into the moving parts above. It also needs to provide this tension regardless of whether there are thirty or a single round sitting on top of it.

Folks in movies often talk about “clips.” A clip is something you put in hair. There was a time when rounds came stacked together in a clip for ease of loading into a fixed magazine on the rifle. That time was World War II, and it was a long time ago. Stop talking about clips.

There are other mistakes which Hollywood makes when it comes to magazines. Usually, heroes will throw away their magazines when they run out. This is pretty dumb, since you’re probably going to want to reload it with fresh rounds at some stage. You probably only have a handful of magazines.

Besides, throwing them away will get you in trouble with the quartermaster. Normal drills for someone like James Bond, I suppose, but not the kind of care for our equipment which we ought to be modelling.

We’ve covered manual, Cycling energy source is the most fundamental characteristic of a weapon. With that in mind, we can take another look at our classification.

Different types of gun (Reprise I)

Making sense of energy, time, and velocity

When we see firearms in action, either live or on videos, everything happens too quickly for our little monkey brains to make sense of it. Guns don’t use incomprehensible technology, they just operate very fast: outside the normal human parameters of perception, so they can seem like magic to us.

Let’s try a trick to get a proper understanding of how guns really work. We’ll need to take an imaginary trip down to the millisecond scale, where each “beat,” or perceived second, lasts only 1/1,000 of that time. In this world:

Now that we’re settled into our slow realm, let’s go to the firing range with an FN MAG, also known as a GPMG: general purpose machine gun. We have a fifty-round belt for this bad boy and the authority to let rip which we trip on slow time perception.

The weapon has a 50-round belt of 7.62 mm ammunition. Normally such a paltry amount of ammo would cycle through a machine gun like this in about four seconds, but with our perception running x1,000, with each beat lasting a millisecond, things will look and feel quite different. Let’s open fire.

Despite our preparations, this takes quite a while. Once your brain makes the decision to fire, it takes about ten beats for the nerve signal to travel from your brain to her finger, and another forty for your finger to squeeze the trigger.

You can follow the sequence with this excellent animation of the internal parts of an FN MAG:

Once the trigger moves back far enough and trips the “sear” (timestamp: 0:19), it takes about 50 beats for the breech block to move forward, extract a round from the belt, guide the round into the chamber of the barrel, and strike the base of the round with the firing pin.

It takes two beats for propellant in the cartridge to start burning, which builds up pressure inside the round and forces the bullet out the front end. The bullet takes another two beats to travel down the barrel, reaching a speed of 840 mm (about 2.5 feet) per beat by the time it leaves the front of the weapon—a slow walking pace.

As the bullet escapes and lazily travels downrange, the moving parts of the gun are starting their rearward journey. Once the bullet passes by a little porthole near the front of the barrel, the accumulated high-pressure gases behind it rush into this hole and push on a piston. The piston moves backward and, using a clever locking mechanism, keeps the bolt sealing up the back end of the barrel for long enough (about five beats) for the pressure of the gases to drop to a safe level. This is a typical gas-operated system.

Now the “actions” of the weapon are moving backwards, propelled by the momentum of the hot gases, at a speed of about 25 mm per beat, reaching the back of the weapon and compressing the giant spring after 20 beats.

Provided that your finger keeps the trigger pulled—and it’s not easy to do otherwise—the gun will repeat its deadly cycle: 50 beats to bring a fresh round into the barrel, two beats to start the gunpowder burning, another two beats for the bullet to leave, and 20 beats for the breech block to go back again to start a fresh cycle. At this stage, the first bullet is about 60 metres downrange, and less than a fifth of a second has passed in real time.

The advantage of rifling

There’s even more extreme engineering when it comes to what the bullet and the barrel experience. Most modern guns force their bullets down a barrel that’s ever so slightly too tight for them. Why? To impart spin on the bullet. Let’s look at why this is a good thing.

A bullet which spins quickly as it travels through the air is more likely to stay on its intended course and not veer off wildly in some other direction. This is clearly a good thing, and a step up from the early days of firearms.

A spinning bullet works better for the same reason that a spinning top doesn’t fall over: the gyroscopic effect. Any little disturbance in the air, which would cause a non-spinning bullet to tumble wildly, turns a spinning bullet around a second axis instead, in a motion called precession:

Spinning bullets are so much like spinning tops that there’s a YouTube trend of wonderful idiots firing pistols into ice to see the bullets bounce out and behave like little spinning tops. I say “idiots” because this is not safe, and “wonderful” because it gives us this amazing phenomenon:

Bullets need to spin fast enough to keep them from “falling over” into the airflow (i.e. tumbling). You can see at the end of the clip above when it finally runs out of energy and topples. There’s no point in spinning them any faster than this, however, since it brings no extra benefit10. It takes energy to spin up the bullet (more on this below), so the spin rate is carefully selected to be just right.

How do we achieve spin?

Gun designers make bullets spin by engraving the inside of the barrel with grooves:

The bullet or shell is ever so slightly wider than the distance between the tops of the grooves, so they grip onto the projectile and make it spin as it accelerates down the barrel. This leaves discernible imprints on the soft copper jackets of a rifle round:

The imprint on the bullet will include any micro-imperfections in the gun barrel’s rifling. This means that bullets can be forensically matched to the gun barrel which fired them, or at least to the tool which made a series of barrels. This is just a consequence of rifling and spin-stabilisation and is not a design feature of rifles.

What do the movies say?

We’ve seen that spin is good, and rifling causes spin. As well as spin, bullets precess, i.e. their nose rotates around a fixed point in front. This precession also has a second-order wobble on top of itself called nutation. If we slowed down time and put a light trail on the tip of the bullet, it would draw a path something like this:

This is something which, as you might expect, Hollywood doesn’t always get. Sometimes we don’t see any spin at all11…

…and other times, we see far too much12:

What we don’t see, because admittedly it would be more difficult to animate, is the wobbling of the bullet as it travels and spins. It would make for a cool shot though. Then, if the filmmakers wanted to get graphic, they could show a bullet starting to tumble just before it hit someone, for maximum damage.

This focus on bullets can distract from the downright ludicrous depictions of firearm (especially pistol) accuracy which we see in the movies. Let’s pick that up in the next section. If you want to read more about bullet spin and so-called “external” ballistics, then check out my article on this topic.

The human limitations of firearms

The effectiveness of a firearm is usually determined less by the cold, hard engineered steel of the weapon itself and more by the soft, squishy, biological entity which operates the trigger.

Pistols, in particular, are used to magical effect by heroes in film and TV. I’ve written a full article about this, but here are some of the main messages.

Pistols accuracy: real vs. Hollywood

Improvements in pistol technology led to only incremental improvements in precision. The most notorious real-life example of this is the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, in 1881. Four lawmen faced four outlaws from a distance of six feet (2 m). The eight men fired about thirty shots in thirty seconds, mostly from revolvers. There were nine hits, including one from a shotgun. This gives the pistols an accuracy of just over 25% from 2 metres:

Still, this doesn’t stop Hollywood from giving pistols some sniper levels of accuracy:

For one more contemporary example of the inaccuracy of pistols, let’s look at a gun battle between eight FBI agents and two criminals in a Miami suburb in 1986. The shootout ended with both suspects dead, along with two agents. Five more agents were wounded. The perpetrators were armed with a rifle and a shotgun, whereas all bar one of the agents were using pistols. The battle happened at close range, between 5 and 20 metres:

Still in denial, Hollywood screenwriters continue to show improbable trick shots, usually by the heroes:

And, finally, there’s this absolutely spectacular contribution from Steven Seagal:

Yes, you saw that correctly. He shot the flare out of the dude’s hand, then shot the shot-off segment of flare in mid-air before it hit the gasoline puddle. Why? Presumably to show off his magic pistol, because I can see no other logical reason.

It’s hard to hit a target with a handgun. If you’ve never tried it before, take my word for it. All else being equal (and it’s not, see next section), a pistol is harder to aim than a rifle:

The first two factors—more points of contact and a longer sight picture—make the shooter more precise and more accurate13. The third factor, the barrel length, makes the weapon more precise.

The best pistol shooters in the world (or, at least, the best Olympic shooters, as per the International Sport Shooting Federation) compete to hit five 13 cm (~5″) targets from 25 m distance in four seconds, with a score of four hits considered good, and two or three hits middling (here’s an example from the 2023 ISSF World Championships in Baku). Olympic sport shooting is not the only shooting discipline out there, but it is easily measured and so we can compare the feats of our Hollywood heroes to the best shooters in the real world:

When I wrote this first, I was disappointed that some of the above shots seemed more plausible than I had initially expected.

However, I didn’t account for movement of either the target or the shooter, and this is important: we’ll come back to this.

In any case, while we might argue that individual shots or groups of shots are on par with ISSF Olympic champion levels, we stretch disbelief too much when all of our heroes’ shots are this good. If they really were better than Olympic shooters, then one wonders why they didn’t become Olympic champion shooters instead of cowboys, secret agents or hitmen, all of which must be tougher jobs with pretty poor conditions and limited benefits (with the exception of secret agents, they probably have a decent public sector pension—but I digress).

With miraculous pistol accuracy ubiquitous in film and TV, it’s nice to see filmmakers actually pay heed to any degree of realism. One example I like is at the end of In Bruges:

It’s literally a long shot, and they both know it. Okay, Colin Farrell is a bit too blasé (he could try lying down to present a smaller target), but he knows enough about pistols to feel safe. Ralph Fiennes takes his time, aims carefully (I estimate the distance is about 20 to 30 m), and gets lucky, which you can see from his expression. Lucky breaks do come, but you can’t show us a dozen “lucky” shots in quick succession and expect us not to throw things at the screen.

A bigger sin is where filmmakers show us shots that go beyond the extremes of human ability, and actually break the physics of ballistics.

The limitations of physics

There are some out there who hold to higher standards. Prepared Gun Owners rubbishes the idea of an acceptable level of “combat accuracy” (i.e. a lower standard just to get the job done). They prescribe no more than a 4″ group14 at 25 yards.

To put it another way, four inches at 25 yards is an angular width of 16 minutes (a minute is 1/60 of a degree. In marksmanship, this is referred to simply as 16 MOA (“minutes of angle” or “minutes of arc”)15:

By the same logic, the top Olympic ISSF shooters hit a 5″ target consistently at 25 m in rapid fire, which is equivalent to 20 MOA.

What if our shooters were perfect? If we removed all human error and unsteadiness in holding a pistol, then what kind of precision could we get from a pistol?

Well, another source (The Hunting Gear Guy) has done the analysis and reckons that 4 MOA (1″ at 25 yards) is the “mechanical accuracy” for a custom bullseye pistol, with most consumer pistols being 6 to 15 MOA.

My own back-of-the-envelope method involves comparing barrel lengths, since this determines bullet precision (albeit not necessarily in a linear way, but that’s the assumption I’m making here). A rifle barrel is about 4-5 times longer than a pistol barrel, and rifle precision can reach 1 MOA, according to Gun Digest: “If a rifle could produce a 1-inch group of shots at [100 yards], aka a 1-MOA group, it was considered an accurate gun.” This means that 4-5 MOA would be an accurate pistol, which ties in with the higher end of the Hunting Gear Guy’s estimate.

Let’s say a pistol’s mechanical precision is 6 MOA. In other words, if you placed it in a vice, this is the spread you’d get on your rounds. With that in mind, let’s examine how some of the scenes above compare with this idealised, best-case situation:

The effect of movement

When I looked at some of the pistol feats above, I was a bit taken aback by how plausible they were. But, as I mentioned there, I hadn’t accounted for movement. And this makes a huge difference. There are two types to consider: the movement of the shooter and movement of the target.

The latter is unavoidable (you can’t politely ask the enemy to stand still while you take aim), so we train for this (although it’s not tested for the standard pistol practice). There are two ways to hit a moving target, and the direction of movement is crucial:

For the other type, the movement of the shooter, this is generally avoided: you exclusively practice firing while in a stationary position, which lets you support your weapon and aim down the sights. When you move, you move quickly, and you keep your finger off the trigger. Your buddies are firing while you’re moving.

Okay, but let’s say you have to shoot on the move, as many Hollywood heroes feel the need to do. What effect does movement have on your precision?

I lack firm data to back this up: the following is based on my own experience and intuition. So please take it with a grain of salt, and feel free to add your own two cents in the comments. Having said that, here’s how I would quantify the added difficulty of movement:

- Target is moving: 2 to 3 times more difficult to hit

- Shooter is moving: 10 times (yes, really) more difficult to hit

- Shooter is on a moving platform but is stationary themselves: 3-5 times more difficult to hit

These multipliers are, well, multiplicative, so if you’re moving yourself and firing at a moving target, I would say it’s 20 to 30 times more difficult to make the equivalent shot. And, for the sake of absurdity, if you’re moving while on a moving platform16, shooting at a moving target, you’re going to be 60 to 150 times less precise. Or accurate. At that stage, the difference doesn’t really matter!

Hollywood loves heroes with pistols, but they neglect the human and physical limitations of these weapons. This shows how they don’t understand a basic fact about guns: different types have different uses.

Understanding the roles of different weapons

The purpose and role of pistols

A pistol is not just a smaller, easier to conceal rifle. As far back as the flintlock technology of the seventeenth century, muskets and pistols were distinct weapons, carried by different types of soldier for different ends. The pistol evolved as a weapon for horsemen, and it complemented their existing weapons, which were the sword and the lance. The pistol was not a ranged weapon designed for accurate fire. It was designed to fire at very close range (but just out of pike stabbing distance) into a wall of infantrymen, or at even closer range into an individual target:

Note how close the firer and target of the pistol are! They are clearly a close alternative to the sword, and probably about as effective.

Technology has, of course, progressed for all firearms since the scenes above, and similar technologies have been incorporated into handguns and what we now call “rifles”, e.g. integrated cartridges, smokeless propellants, magazines, and even rifling. They remain distinct weapons, however, and some of the main technical differences are:

Broadly speaking, rifles are the primary or default weapon for an infantry soldier. As you can see above, they are effective to a few hundred metres, further if the section is firing together17. Many infantry soldiers use heavier weapons such as mortars, heavy machine guns, or anti-tank weapons, but they will normally always carry a rifle as their primary weapon.

Pistols, on the other hand, are not a primary infantry weapon, and never have been, because of their different characteristics outlined above. What are they used for? Well, their main (only, really) advantage is that they are small and therefore easy to carry. This makes them useful for two purposes:

- As a sidearm for cavalry (this was true when cavalry rode horses and carried lances and swords, and is still true when cavalry drive tanks),

- As an officer’s weapon, since an officer’s soldiers, and their rifles, are his/her tool of battle.

Since officers traditionally also rode horses and carried swords, there is a bit of crossover here too. We can see in Blackadder Goes Forth how the officer’s tools of battle differ from those of his men. Although this scene is obviously comic, it is the most poignant of the series, and provides the ending note:

In the military, the pistol is still a symbol of authority. During my officer training, the pistol was the last weapons system we trained on, having trained with the rifle, light machine gun, grenade launcher, grenade, and section-level anti-tank weapon. We learned the pistol at the same time as we learned sword drill, about two weeks before being commissioned. In fact, the two are probably about as useful as battlefield implements of violence, although the pistol is admittedly more compact.

Apart from exercises and deployments, my main occasion to carry (“wear”) a pistol was in barracks as orderly officer, which is a daily duty officer role. The orderly officer and orderly sergeant carry pistols to denote their authority and indicate to others that they’re on duty. When a mate covers duty for a few hours so that you can go for a run, they are said to be “holding the pistol”.

This is all well and good, you say, but what about police forces? They carry pistols as their standard weapon. Does the same logic hold? Well, firstly, this is not true universally. Where I come from, police are routinely unarmed. I remember the first time travelling to the USA, as a child, and staring wide-eyed at cops with guns. It was scary to think of people having that casual ability to inflict violence (this was long before I had exposure to real guns are realised how ineffective pistols are as a tool of violence).

This was pre-9/11, 7/7, Bataclan, Madrid, and other such attacks. Now, police forces in Europe are more likely to carry firearms. However, it’s still not routine and, crucially, you are as likely to see them with submachine guns or even assault rifles as pistols: weapons which are far more suited to the range of tactical situations which might require a kinetic18 response from the police.

Even where police carry a pistol as standard, however, it would be wrong to see this as equivalent to an infantryman’s rifle. An infantry soldier’s rifle is the primary tool for their job19. A police officer’s pistol is not, at least I would hope, the primary tool of their job. Their physical presence and their authority or “badge” are the most important tools in their toolbox.

A pistol is not a tool for targeting criminals at a distance, and any police officer who uses it like this is either poorly trained or a film/TV character. Why? Because Hollywood thinks that pistols are like rifles.

Hollywood pistol myths

Film and TV writers prefer to think of pistols as “rifles, but smaller.” They have similar range, accuracy, magazine capacity, and target effect, but conveniently stow away into a trouser or jacket pocket when not in use.

There are (as usual with film and TV) multiple levels of unreality going on here. Firstly, they make a hash of describing how pistols are employed as part of an overall unit, i.e. there is no distinction between the pistol, shotgun, and the rifle.

Secondly, they expect all heroes who are cops or agents to have levels of pistol marksmanship on par with world champions. Thirdly, they sometimes break even this fragile layer of reality with levels of accuracy and precision which exceed the technical possibilities of pistols.

I’ll deal with the first layer on this week’s post and go down the rabbit-hole of marksmanship and minutes of angle next week—watch this space.

The best way of illustrating this misunderstanding of how pistols fit into the broader tactical scenario is through some examples of gross misuse of pistols in film. There are two species of this. The first is the “pistols akimbo” setup where everyone has a pistol drawn and is pointing it at the target. Nothing gets in the way of your pistol and the target: not distance, not movement, not your buddy cop who’s standing almost exactly in front of you, not the cops who are standing on the other side of the target, also with pistols drawn. The aim is to achieve a hail of inaccurate lead. Who knows, some of this lead might actually hit the target:

The second is the “Freeze! Police! Hands in the air!” scene, of which some examples below. The cops are usually hiding behind the door of a car for cover, or the engine block (the latter is a better choice, since it will stop a lot more lead than a sheet metal door). They might also employ the overlapping arcs of fire we’ve seen above, showing a casual disregard for the safety of their buddies. And if some of their buddies have rifles or shotguns, who cares? I’m still going to point my peashooter. The more lead the better, right?

The worst example of all, however, has to be the shootout scene from Heat. I feel slightly conflicted about this because, in many other respects, it is a realistic depiction of squad-level fire tactics, at least on the part of the baddies. However, I can’t defend the cops using their pistols to fire from at least 50 m away, which is simply too far to lay down any effective fire:

Perhaps this is the point, i.e. we are being shown how slick the bank robbers are compared to the LAPD?

Look, I get it. No-one likes carrying a rifle, because it’s heavy, it’s clunky, it occupies your hands, and it needs cleaning. Pistols, by contrast, are small, sit in a holster, leave your hands free (because they stay in the holster), and rarely need cleaning (because they are rarely fired).

It’s no wonder that Hollywood characters prefer carrying pistols to rifles: in that respect, they are just like millions of officers and NCOs who jump at the convenience of the pistol, not to mention the fact that it marks one out from the crowd.

However, take the officer away from the truculent bosom of his/her platoon or company, and things change. Without one’s soldiers to direct, then an officer with a pistol is quite a helpless creature. If the goal is self-preservation, then every sane person would carry a rifle20 as well as (or instead of) a pistol.

In Hollywood’s classic way, the symbol of authority and importance (the pistol) got passed on and coded to the heroes of the film, be they military, cop, or civilian. At the same time, since the hero is generally operating alone or with a small team, they need the “oomph” that a rifle gives you. This is why our heroes end up with seemingly magical pistols that can take out an entire company of enemy goons or do trick shots from improbable or impossible distances, like we discussed in the last section.

Different types of gun (Reprise II)

- Here are just a few examples:

https://www.nrafamily.org/content/how-do-guns-work-part-1/

https://youtu.be/flYYG65yW5I?si=ZOIcjexNHZysrX60&t=110

https://www.reddit.com/r/explainlikeimfive/comments/bwrhvi/eli5_how_do_guns_work/

https://www.luckygunner.com/lounge/blowback-versus-recoil/

↩︎ - I’m a proper freedom-hating European, but I’m comfortable with Imperial units. Honestly. ↩︎

- <Sigh>. Yes, I see you over there, powder actuated tools, raising your hand. There’s always one, isn’t there? ↩︎

- Because, and this may be news to you if you’ve never used one, but pulling back the string on a bow is hard. It’s supposed to be. It’s how an arrow can get lots of speed. It’s why, as Bret Devereaux on ACOUP points out, these scenes of fantasy or ancient battles where archers “volley fire” are pure nonsense. ↩︎

- Prompt: “Can you make me four simple powerpoint icons please? They should be black on white background. They are: 1) An ancient spearman 2) An ancient archer firing his bow and arrow 3) A medieval crossbowman 4) An early modern musketman” ↩︎

- Rough assumptions: energy density of black powder is 3 MJ/kg, a person works about 2,250 kcal per day (~9 MJ), and a musket load of powder is about 90 grains, or 5 grammes. ↩︎

- In firearms engineering, a “grain” has actual meaning. It’s a measure of weight equivalent to about 0.065 grammes. It was on old Imperial unit used for other measurements back in the day, but that day has passed: now you see it only to weigh bullets and bullet propellant loads. ↩︎

- I wasn’t able to find the original source for this image, so please let me know if you are aware. I’m sure I’ve seen it before, though, but there’s a non-zero chance this is AI-generated slop based on real plates from an old manual. I feel like some of these drill movements might be a bit superfluous, like #143: “Stand there looking suave and satisfied with yourself,” or #96: “Wave your equipment about like a lunatic.” ↩︎

- In the diagram above I’m simplifying what was something of an evolutionary process, with integrated paper cartridges, for example, forming intermediate steps. ↩︎

- It may actually damage the bullet through centrifugal forces if the spin is too extreme. ↩︎

- Admittedly, the camera and probably the viewer is looking at Gal Gadot much more than the bullet. No complaints there. This second clip, with the bank robbers, suffers from the “single-speed slow motion” effect I’ve written about in my blog. If Wonder Woman really did move that poor schmuck’s head out of the way of a bullet, the sudden impact of her hand on his head would be as bad, or worse, than the bullet. ↩︎

- Compare the spin “trails” (also not a thing) with the slower rate of spin we saw in the high-speed video above. I feel bad nitpicking this scene though, because it’s so freaking iconic, and they made a decent attempt. ↩︎

- Yes, there’s a difference. Accuracy is about getting close to the intended target, precision is about getting multiple rounds to land consistently close to one another. There’s a good explainer here. You can be precise without being accurate, and vice versa. The very same principle applies to numbers: if I estimate my holiday spend to be €578.98, and the final figure is €810.40, then I’ve made a precise but not at all accurate estimate. If, on the other hand, I say it’s “about €800”, then I’ve made an accurate but not precise estimate. In this context (and in many), accuracy is more important than precision. In shooting, both are important, but bad accuracy can be more easily addressed by zeroing the weapon or changing the point of aim. ↩︎

- A “group” or “grouping” is a marksmanship term meaning the size of the notional circle into which the bullet holes on your target will fit. ↩︎

- If my mixing of metric and imperial like this bothers you, then I’m sorry: I empathise, but let this be your harsh welcome into the world of firearm discourse. Besides, for our rough purposes, a yard is the same as a metre. We’re estimating distances from single frames, for heaven’s sake. ↩︎

- Let’s say you’re running along the top of a train, shooting at someone speeding in a car next to the train. Don’t tell me this has never been attempted in movies. ↩︎

- If you’re wondering why a group of soldiers has a greater effective range than a single soldier, it’s not because any individual round is more accurate, but the combined effect on the enemy of more rounds landing nearby, even though they are less accurate because of the long range, is enough to get them to keep their head down. The goal of infantry rifle fire is not necessarily to hit your target, but to get them to keep their head down while your own forces move closer and close with them. If course, if you hit them in the process, that’s a big plus. ↩︎

- This is a piece of military jargon which means “shooty”. ↩︎

- I’m talking, of course, about a conventional battlefield scenario. Once you bring in counter-insurgency, peacekeeping, and peace enforcement, the requirements change a bit. This is one of the reasons these types of operations are notoriously difficult. ↩︎

- In practice, at squad and platoon level, commanders will carry their rifles (even though they might not use them much) for this very reason: they are operating in small groups, potentially in fireteams of two or four, so every rifle counts. ↩︎

Leave a Reply